Sunday, May 24, 2020

Gordon Grdina Makes Music That Is Important for Humanity

Saturday, May 23, 2020

Catching up with Gordon Grdina…again

By Nick Ostrum

Oudist and guitarist Gordon Grdina spanned the new year with three releases that caught my ear. So, here is a second compendium of Grdina’s recent work to complement Eyal’s from September 2018. Apparently, it is about time. (Editor's note: Eyal will be catching up again, tomorrow!)

Matthew Shipp, Mark Helias, and Gordon Grdina – Skin and Bones (Not Two, 2019) *****

I am sorry I missed this last year, because this would have hovered around the top of my year end list.

Skin and Bones is the first of two piano trios, consisting of the incomparable Matthew Shipp on keys and Mark Helias on bass. The title comes from a concert series dedicated to experimental music that has brought a slew of contemporary free jazz (and related music) luminairies to Canadan’s Okanagan. In 2018, trio consisting of Shipp, Helias, and British Columbia native Gordon Grdina were among them.

Inspired by their clear rapport, the trio decided to cut a studio album of completely improvised material, judging by the titles, apparently inspired by boxing. But, starting with the first track, it is clear they are doing much more than providing the soundtrack to some bout of fisticuffs. It begins with a starkly romantic run by Grdina that quickly gets swept up in a gust of piano and pizzicato bass. Over the course of the first track, “Bob and Weave,” the musicians seem to oscillate more with the vagaries of the weather than bob and weave with the determined pugnacity of a boxer. Indeed, there seems more surrender to melody and course, and some sort of naturalism, in this piece that may be absent the controlled and aggressive space.

And, it seems, the rest of the album follows with a series of boxing-themed titles that, if the listener were to embrace the music’s naturalism, relaxed flow, and titular double entendres (“Stick and Move,” “Feather Weight” [rather than featherweight]). Indeed, it is not until the stormy “The Onslaught” over 40 minutes into the album that I hear any real aggression. Tension and virtuosic rapidity, of course, pop in and out of previous tracks. Most, however, are slower, more contemplative and, even, listless (“Solitary Figure”), and lyrical. That is not to say that these traits are entirely absent from boxing; the most obvious example is Muhammed Ali’s marriage of verbal and physical poetry, and his vernal analogy of the boxer, the butterfly, and the bee. And, sure, we can trace this back through Hellenistic ideals of naturalistic male beauty and performance. I am cannot say the trio intended such a reading, but this album seems to draw similar connections between the humanly brutal and the deceptively whimsical natural realms. And beyond this album contains 72 minutes of absolutely engaging and absolutely stunning improv. Then again, from these three musicians, would one expect anything less?

Gordon Grdina Quartet – Cooper’s Park (Songlines, 2019) ***1/2

This quartet seems to be working its way into one of Grdina’s more stable working groups. Coming off their 2017 release Inroads, Cooper’s Park is a solid collection of five, primarily mainstream jazz pieces. Although the musicianship is impeccable and them music periodically breaks into stilted melodies and abstract group improvisations, this album shines less than the other two reviewed here. Drummer Satoshi Takieshi lays swinging grooves over which Oscar Noriega navigates his reeds and through which Ross Lossing weaves his keys (piano, Rhodes, and clavinet). For his part, Grdina gives a solid performance and shows that he can rein in his more exploratory impulses. Because of the music’s creative conventionality (neologism or nonsense?) and its gentle dynamism (especially the in tracks like “Seeds” and the titular “Cooper’s Park” the effort is much tighter than Grdina’s more freewheeling releases. And, Cooper’s Park does venture beyond the contemporary funk-laced jazz into prog rhythm and restrained free jazz discordance. At times, as in the enchantingly delicate ten-minute introduction to “Wayward”, first Grdina, then Lossing, followed by Noriega and Takieshi shine through an understated economy rather than forceful superfluity of melody and consonance. These excursions and extended blissful passages, however, remain the exception and the result somewhat less compelling than some of Grdina’s more out recordings.

Gordon Grdina’s Nomad Trio – Nomad (Skirl Records, 2020) ****½

Nomad is the newest of the bunch and the second piano trio. On this disc, Grdina is complemented by Matt Mitchell (who, especially as of late , has been showing himself to be one of the premier pianists in the scene) and Jim Black on drums.

Coming off listening to Skin and Bones, it is clear from the very first notes of the opener “Wildlife” that Nomad is a different beast. It has a more rhythmic, free rock vibe. It has more recognizable melodic progressions and harmonies. Some of this may be attributable to the fact that Grdina composed all tracks himself. That said, Nomad is still open and heavily improvisational. Grdina may set the direction, but Mitchell and Black help take us there. Take “Wildfire.” It begins with discordance. Grdina meanders around his electric guitar; Mitchell plods around a plucky series of chords and rhythms; Black fumbles around and crashes magnificently. It is difficult to hear what is composed apart from maybe the mood of the starting point, the basic trajectory of the piece, and a coda at the end. Then again, the piece is unified. Despite a lot of freedom to wander, the track moves to a singular effect. Most other tracks, including the eponymous “Nomad,” are of a similar ilk, even as their compositions come out more clearly in repeated melodies that lay the groundwork for the improvisational meat that follows. This is fusion, tending toward thick guitar lines and stilted, heavy melodicism, minus the soaring (and showy) flourishes that the latter label evokes. It is not that the band plays with Bauhaus/new objectivity instrumentality or shuns displays of virtuosity; rather, when they do embellish, they do so with purpose. The end-products are more meditations on converging styles or a mood than the start-stop melodic jumbling that a lot of composed guitar music of this type tends toward. The final cut, “Lady Choral,” is a seductive, Iberian outlier, wherein Grdina, unplugs and turns to the oud for an extended solo. The result is a sparser, but deeply emotive piece that seems to reference classical Arabic music even more than the heavier guitar music that drives the rest of the album. A moving and meditative departure, and perfect conclusion to a compelling excursion to the fault where hard(er) rock and free jazz merge (or deviate).

Monday, September 24, 2018

Latest Releases of Guitarist-Oud Player Gordon Grdina

Gordon Grdina’s The Marrow - Ejdeha (Songlines, 2018) ****½

Gordon Grdina Quartet - Inroads (Songlines, 2017) ****

Gordon Grdina - China Cloud (Madic Records, 2018) ***½

Thursday, October 24, 2024

Two Gems from Gordon Grdina

By Nick Ostrum

This is becoming a pattern on FJB. Gordon Grdina drops a few albums, and we cover them, usually with high praise. This review will continue in that trend.

Guitarist and oudist Grdina has become a singular voice over the years, whether as a solo artist or in various larger ensembles, whether performing his own compositions, those of Tim Berne and other composers, or just improvising. Although he is tirelessly active, he is deliberate about what he releases on his Attaboygirl Records. These tend to be albums, in the sense that they each are thoroughly inspired and, despite the improvisation, to drive toward singular overarching impressions.

Gordon Grdina’s The Marrow with Fathieh Honari (Attaboygirl Records, 2024)

Dedicated to the late Persian-Canadian musician Reza Honari, The Marrow with Fathieh Honari is a case-in-point. Already with two releases under their belt, the core of The Marrow (Mark Helias, Hank Roberts, Hamin Honari (Reza Honari’s son), Grdina) have been at it for a almost a decade. Here, they are joined by the elder Honari’s wife Fathieh Honari on vocals.

It begins with a somber duet between Grdina, on oud for the entire album, and Fathieh Honari. Then come the drums (Hamin Honari) and Helias and Roberts’ strings, which transform the initial incantation into a processional jaunt with oud and cello doubling and Honari and Helias steadily driving from behind. Soloists briefly sprig out wispy tendrils, but the core remains tight. Fathieh rejoins and, as with Emad Armoush’s contributions to Grdina’s Arabic-inspired Haram ensemble, carries the project to a realm ethereal. Persian is beyond me, but that might just add to the mystery that The Marrowevokes. Indeed, when Fathieh ululates, she elicits tinges that go beyond the flesh and bone, to the marrow.

I am tempted to take that analogy further. In contrast to Duo Work (below), Marrow is based around a center, based on Middle Eastern scales and, presumably, song structures. It evokes the intangible: memory, sorrow, hope, fantasy (at least in its inscrutability to this listener), phantoms, and simply being. That is a tall order, but the shaken percussion that inaugurate the second selection, Raqib, the syncopated vamping of Break the Branch, the dreamy drone of Qalandar (which becomes genuinely joyful after the first two minutes), and the simultaneous fullness and fogginess captured in each of these pieces all speak to a state of meditation, either a deeply interior or out-of-body cognitive trip. Even in a succession of strong releases The Marrow with Fathieh Honari stands out.

Gordon Grdina and Christian Lillinger – Duo Work (Attaboygirl Records, 2024)

Duo Work is another album in the sense of vision and coherence though, aesthetically, it is altogether different from The Marrow. None of Duo Work is composed (as far as I can tell) or calming, sentimental or mystical. Rather this is free-form fusion rock n’ roll noise, through and through.

The overwhelming impression I get from Duo Work(with Christian Lillinger with whom Grdina has worked in Square Peg and with Mat Maneri on Live at the Armory), is a delicious mix of late 60’s Frank Zappa (with more overdubbing and effects) and late career Sonny Sharrock pared down to a duo format with a drummer miraculous endowed with an extra arm or two. All the things one loves about Lillinger are here: his unassailable precision, his unique sense of rhythm within rhythm within rhythm, his strangely alluring time-keeping, his big sound. From Grdina, one hears his precision (of course!) but also his apparent roots in the more experimental reaches of fusion. This is Interstellar Space for guitar and drums, segmented, stripped of the modal celestial appeals and strewn about with a playful urgency of John Zorn’s early crossovers into metal and grindcore. Or maybe it’s a truncated Shut Up and Play Yer Guitar, cut, glitched, modernized, and performed all at once by a band of two. Either way, it is one of the most exciting releases I have heard all year.

I am not sure which, but at least one of these albums is going to be on my year-end list.

Monday, September 14, 2009

Gordon Grdina - East Van Strings - The Breathing Of Statues (Songlines, 2009) ****

I knew Vancouver guitarist and oud-player Gordon Grdina from his debut album "Think Like The Waves", with nobody less than Gary Peacock on bass and Paul Motian on drums. Quite a feat for a young musician, and one that illustrates the trust these jazz greats have for his skills and potential. And although the album got some favorable reviews, it was still very rooted in bop. Next to his jazz albums, he also created more Arabic music with Sangha, genre-fusing music with Box Cutter, and now he explores the possibilities of a string quartet, with Jesse Zubot on violin, Eyvind Kang on viola, and Peggy Lee on cello, with of course Grdina playing guitar and oud, moving the music away from jazz and into modern classical music and avant-garde, with strong influences from Arabic and Persian music. The combination is not bad at all, it adds the right level of drama and sadness, well balanced with the more cerebral explorations of new sounds and sound combinations. The most beautiful piece is the long title song, the album's pièce-de-résistance, on which the oud's warm plaintive phrasings is supported by the hypnotic and melancholy strings. Despite the typical sound of the line-up, for some ears the breadth of the musical journey this quartet takes may still be too far-reaching, ranging from the ancient traditions of the middle-east to the very abstract, at times dissonant modern music, but Grdina manages to use that scope to his advantage, laying bare an austere yet emotionally expressive aesthetic that unites the various genres on this album. A strong achievement and a nice listening experience.

I knew Vancouver guitarist and oud-player Gordon Grdina from his debut album "Think Like The Waves", with nobody less than Gary Peacock on bass and Paul Motian on drums. Quite a feat for a young musician, and one that illustrates the trust these jazz greats have for his skills and potential. And although the album got some favorable reviews, it was still very rooted in bop. Next to his jazz albums, he also created more Arabic music with Sangha, genre-fusing music with Box Cutter, and now he explores the possibilities of a string quartet, with Jesse Zubot on violin, Eyvind Kang on viola, and Peggy Lee on cello, with of course Grdina playing guitar and oud, moving the music away from jazz and into modern classical music and avant-garde, with strong influences from Arabic and Persian music. The combination is not bad at all, it adds the right level of drama and sadness, well balanced with the more cerebral explorations of new sounds and sound combinations. The most beautiful piece is the long title song, the album's pièce-de-résistance, on which the oud's warm plaintive phrasings is supported by the hypnotic and melancholy strings. Despite the typical sound of the line-up, for some ears the breadth of the musical journey this quartet takes may still be too far-reaching, ranging from the ancient traditions of the middle-east to the very abstract, at times dissonant modern music, but Grdina manages to use that scope to his advantage, laying bare an austere yet emotionally expressive aesthetic that unites the various genres on this album. A strong achievement and a nice listening experience.The Gordon Grdina Trio - If Accidents Will (Plunge, 2009) ***

The Gordon Grdina Trio is a different story. Accompanied by Tommy Babin on bass and Kenton Loewen on drums, the guitarist demonstrates the wealth of idioms he masters, but a little too much. True, each piece of the album is well-played and has musical merits of its own, but it is very difficult to find the commonalities between a 12-minute long oud improvisation - beautiful though it may be - with the harsh, raw and burning modern electric guitar trio tunes with which the album opens. And then we get the compulsory slow blues, and yes we like the blues, but what is it doing here? And then you also get treated to a more melodic post-bop piece to end the album. All nice, but no coherence. The trio can play, no doubt about it. But mixing it all up is confusing to this listener. The album starts full of promise, but then you get the impression that inspiration got lost, and that the band fell back on the more beaten track. The good news however is that with every release, Grdina seems to come closer to creating his own voice. And that's good progress.

© stef

Monday, March 7, 2022

Tim Berne, Gregg Belisle-Chi, and Gordon Grdina: Five Stars

By Gary Chapin

Tim Berne and Gregg Belisle-Chi: Mars (Intakt 2022) *****

I feel like this duet recording is closing a thesis-antithesis-synthesis loop. In May 2020 Tim Berne released his first solo recording, Sacred Vowels. In June 2021 Gregg Belisle-Chi released Koi: Performing the Music of Tim Berne. A few months ago, I interviewed Belisle-Chi , and he told me that he and Berne had just recorded a duet—which is what we’re reviewing now. A nice arc or circle, but I hope not a closed one, because I’m going to want more music like this.

I don’t always know what’s going on with the com-provisation balance in this type of thing, and I admit that I might be overly fascinated by the creation process of musicians like this. Here we’ve got Tim Berne’s horn, a powerful instrument that can fill any room, and Belisle-Chi’s guitar, an instrument marked by measured gentleness. The production helps it work. The guitar is intimate and personal, the sax surrounds you. Kudos to David Torn.

Belisle-Chi’s approach is baroque in its spirit, though not its content. As he explained in his interview, he took Berne’s sheet music and created skeletons (with guitar fingerings and all) that had him serving bass, harmony, and melody roles all at various times. The improvisation is woven throughout. It’s unpredictable but logical in its form, like the striations in marble.

There is a sense of introspection and conversation; solitude in partnership. Tim’s improvisations are calls for Belisle-Chi’s responses. I’m reluctant to talk in terms of “purity,” but the distillation that takes place on Mars provides a remarkable clarity to Tim’s tunes. Just the brevity of the pieces (only one longer than 5 minutes, and one under a minute) leaves us understanding that nothing here is excess. You feel this is what the tunes really are. Their purest form.

And that’s a fiction the listener brings and probably a bias of my own. At the very least this album—like the other two in the triptych—provides a different window into Berne’s work. And is beautiful in its own right besides.

I wonder when a recorder consort will step up to the challenge.

.

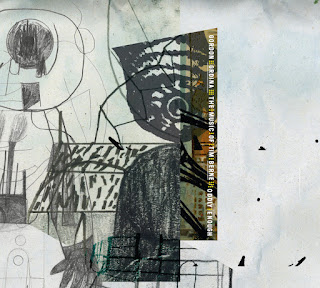

Gordon Grdina: Oddly Enough: The Music of Tim Berne (AttaBoyGirl 2022) *****

When I said in the above review that the guitar brings a baroque sense of order to Berne’s music, I should have said, “Shines a spotlight on the baroque sense of order” or “Amplifies the sense of order.” The order is there in the compositions and you can hear it in all of Berne’s work (it’s one of the defining characteristics). The success of the implementation depends on the performer’s relationship with the compositions.

You can hear all of this on Gordon Grdina’s brilliant Oddly Enough . It is also a solo string player interpretation of Berne compositions, but it’s a multi-timbral, multi-tracked, layered recording. Grdina plays electric/MIDI guitar, acoustic, classical, oud, dobro, and MIDI. David Torn produced this one, too.

It opens on “Oddly Enough,” with electronic percussion feeling industrial on its own, but then two electric guitars come in, one pretty clean the other not, creating a context. The clean guitar states a head, while the other supports with counter-melodies in kind. Gordon is talking to himself here, and it’s pretty fascinating listening in. (Side question: when you talk to yourself, are you you, or are you yourself?) “I Don’t Use Hair Products,” is a lean solo guitar interpretation, classical sounding in approach. “Trauma One'' centers the oud for the first time (with other stringy acoustic things joining), as does the later piece, “Enord Krag.” EK places the oud over (and then under) long, howling electric guitar scaps, hearkening (for me) all the way back to Berne’s elegiac work with Bill Frisell on 1984’s Theoretically . (Still one of my faves. They both seem so young.) It’s a welcome call back. Grdina closes with two more extended “conversations” between various instruments, focusing on melodies in relation to other melodies.

.

Tuesday, December 27, 2022

Gordon Grdina’s Haram - Night’s Quietest Hour (AttaBoyGirl Records, 2022)

It took Canadian guitarist and oud player Gordon Grdina ten years to record the second album of his ensemble Haram, dedicated to the exploration of the Classic Arabic repertoire, beginning with Iraqi folk music and the great era of Egyptian radio music in which Oum Khalsoum and Farid Al Atrash, and now also covering Sudanese music from the '60s and '70s. Haram relies on the same ensemble that recorded its debut album, Her Eyes Illuminate (Songlines, 2012) - Canadian musicians from the Vancouver jazz scene with Syrian-born vocalist and ney player Emad Armoush, and with special guest, guitarist Marc Ribot, who joined Haram for two concerts in Vancouver just before the Covid-19 pandemic hit all.

Night’s Quietest Hour injects fresh, and sometimes even explosive doses of blues, funk and free jazz into the original Aiming compositions, but aiming to keep the spirit of tarab, the ecstatic feeling of elation inherent within these classic Arabic compositions. A few decades ago we called such meetings East Meets West (and vice versa), but Haram does much more. It is not a polite meeting between distant cultures, but the way Grdina and Haram assimilate these cultures and enrich each other, with deep respect for the original compositions and familiarity with the traditional forms and scales. Haram blends these traditions and finds similar sensibilities in the improvisation strategies in Arabic music and in jazz., in an effortless coihesion, The presence of the ever-inventive Ribot, who is not well-versed in Arabic music as the Haram musicians adds a bold sense of danger.

The opening “Longa Nahawand” relies on the four-beat longa and in the melodic mode nahawand, but the duet between Ribot and Grdina, who plays only the oud on this album, turns this classic form, made famous by famous Egyptian composer Riyâdh As-Sambâti, into a sensual, funky blues. The following “Sala Min Shaaraha A-Thahab” (سال من شعرها الذهب, old Streamed Down from Her Hair) by Sudanese singer Salah Ben Al Badiya, enjoys the hypnotic beat of drummer Kenton Loewen and percussionists Tim Gerwing and Liam MacDonal. Ribot adds a psychedelic aroma to the singing of Armoush and the driving beat and brings the song into a cathartic coda. The traditional “Dulab Bayati” is an instrumental, rhythmic piece in the form of dolab and in bayati maqam, attributed to Egyptian composer Muḥammad ᾽Abd al-Raḥīm al-Maslūb. It is interpreted as a series of fast calls - played by Grdina - and answers - by the Haram Ensemble, but when Ribot joins the ensemble he sends this rhythmic piece into stratospheric skies with a wild, distorted solo. Haram interprets one of the most famous and popular Arabic pieces “Lamma Bada Yatathanna” (لما بدا يتثنى, When She Begins to Sway), most likely based on a poem by Andalusian poet Lisan al-Din Ibn al-Khatib, in the poetic form muwashshah of the Nahawand maqam. Here Haram and Ribot improvise over the familiar theme and turn it into an ecstatic free jazz blowout. The last song “Hawj Erreeh” (حوج الريح, Violent Wind) by Sudanese singer Ahmad Al Jaberi becomes an infectious song, with Grdina and Ribot, intensifying the choros with an inspiring, tight duet.

Well worth the long waiting. A great record that demands more follow-ups.

Wednesday, February 5, 2014

World jazz with influences from the Middle-East

As written before, I love Arabic music, I love the scales, the rhythms, the long improvisations and most of all the emotional power coupled with a deep spiritual longing. I also like - not all, but some of it - of the real worldjazz efforts by Arab musicians such as Anouer Brahem, Dhafer Youssef (both from Tunesia), Rabih Abou-Khalil and Marcel Khalife (both from Lebanon), and many more.

Some new albums go in the same direction and are worth mentioning.

Ayman Fanous & Jason Kao Hwang - Zilzal (Innova, 2013) ****½

Although it starts in a very traditional way, guitarist and bouzouki-player Ayman Fanouz and violinist Jason Kao Hwang quickly turn expectations upside down, extracting the ingredients from tradition, deconstructing forms and re-integrating them in another kind of beauty, the one in which new sounds arise from nowhere, shattering the calm contempative nature of the first track into short bursts of agony and distress. "Zilzal" means earthquake, and that is what you get in some tracks.

This is not world music. It isn't jazz either. This is music with ambition. Ambitions of beauty, artistic ambitions, for new forms of sounds, new ways to express things, full of emotional depth, with emotions that are too complex to be canvassed in old forms, too elusive to be captured in patterns, too deep to be expressed in shallow tunes.

Amir ElSaffar - Alchemy (Pi, 2013) ****

Master trumpeter Amir ElSaffar re-writes jazz harmonies based on former Babylonian and Summerian scales and rhythms, with microtonal chord changes. The result is not as gripping as his previous album (check them out on this website) but remain highly recommended for listeners looking for other views on how music may sound, this is worldjazz of a complexity that you rarely hear, even though the overall sound is quite boppish.

With Ole Mathisen on sax, John Escreet on piano, François Moutin on bass and Dan Weiss on drums.

Nashaz - Nashaz (Bandcamp, 2013) ***½

Nashaz is the debut album of the band with the same name and consisting of Brian Prunka on oud, Kenny Warren on trumpet, Nathan Herrera on alto sax, bass clarinet and alto flute, Apostolos Sideris on bass, George Mel on frame drum, udu drum, cajon, pandeiro, and percussion, and Vin Scialla on riq.

Like other musicians such as Rabih Abou-Khalil the ensemble uses middle-eastern scales and rhythms with traditional and jazz instruments mixed. The effect is nice, the playing is good, really good. It is not really ground-breaking, but within the subgenre of middle-eastern influenced jazz, it's easy to recommend.

Listen and download from Bandcamp.

Devin Ray Hoff - The Lost Songs Of Lemuria (2013) ***

A nice album, four tracks, with all four musicians improvising on a somewhat repetitive rhythmic base. With Tomeka Reid on cello, Alex Farha on oud, Frank Rosaly on drums and Devin Hoff on acoustic bass guitar.

Very welcoming sounds and some beautiful improvisations.

Listen and download from Bandcamp

We have reviewed Vancouver-based guitarist and oud-player Gordon Grdina before. On this album he teams up with Mark Helias on bass, Kenton Loewen on drums and Tony Malaby on tenor.

The first track is a deep piece for oud and bass, really strong and very middle-eastern in scales, rhythms and melody. But then Grdina is also a jazz guitarist. So the next track is very jazzy, again a duo with Helias, close to mainstream, gentle and warm. On the third track his guitar sounds a notch more distorted, and when the rest of the band joins the guitar-bass intro, you are almost in full fusion territory at times, full of power and speed and loudness. Or you get complete noise on the avant-garde "Cluster".

Like in several of Grdina's other albums, coherence is missing. There isn't even an effort to come with a single musical vision, no, the listener gets exposed to a whole series of possibilities, but when you try too much you often end up with too little.

Jussi Reijonen - Un (Unmusic, 2013) ***

Another strange album, ranging from middle-eastern meditative music to a prog rock version of Coltrane's "Naima", with in between references of Maurice El Medioni, and very quiet down-tempo new-agey rock music. A strange mix. Like Grdina's album, it is not quite clear what the unity of musical vision is, and if Grdina evolves into more volume and tighter interplay, Reijonen's music goes all quiet and more open.

Jussi Reijonen himself plays oud, fretless guitar, fretted guitar, Utar Artun on piano, Bruno Råberg on acoustic bass, Tareq Rantisi on percussion, Sergio Martinez on percussion, Ali Amr on qanun, and Eva Louhivuori joins on vocals for the last track.

Find out more on the musician's website.

Tuesday, July 2, 2024

Novara Jazz, 21st edition – June 2024, Novara, Italy

Photos by Emanuele Meschini and Edward Roncarolo.

Located in the Piedmont region of Italy, west of Milano, the 21st edition of Novara Jazz, programmed by Corrado Beldì and Riccardo Cigolotti with input from Enrico Bettinello of the Novara-based WeStart organization, unfolded from May 31 to June 9. Its last leg had a wealth of acts in aesthetic unison with the Free Jazz Collective.

|

| Gordon Grdina |

The Broletto is a wide transverse courtyard in the middle of several historic buildings and museums, where the free (as in gratis) evening concerts take place. After a slice of 1940s big band jazz, we move to the place where Canada’s Gordon Grdina and Germany’s Christian Lillinger are getting ready. A last-minute change of venue saw the duo adapt their music, which is carried out on the doorstep of the “Space in the Place” art store on Corso Italia. The dense, tense and loud set is chockful of electronics, both artists equipped with abundant gear – which is rather new to them, we learn. I mostly knew the “gentle” side of Grdina, not so much his electric rock persona, pretty much to the fore here. The subtle, expressive and sometimes explosive drummer and his string agitating accomplice do not allow room for breaks or silence. Their glorious racket fills the otherwise quiet Ligurian streets, whose passers-by and inhabitants either flee in terror, close their windows and shutters, or come out on the balconies and postpone their errands to enjoy the show. The journey through the hurricane is propelled by the hyperactive Lillinger, who nonetheless finds time to comb his hair between millimetric strikes and other spaceship dashboard sounds. The wall of sound approach settles down as the guitarist unpacks the oud, which we do not hear for long as the saturated guitar, abundant drumming and bubbly synth blips quickly resume, in the late warm afternoon.

|

| Alexander Hawkins |

The Alexander Hawkins Dialect Quintet makes its worldwide premiere, prior to hitting the studio in Torino. The hubbub from the nearby restaurant terrace proves enough of a nuisance to impair the audience and musicians’ listening, and Hawkins wisely adapts his demeanor to the situation, often taking his hands off the keyboard to better pay attention to the handiwork of his younger colleagues. Technical constraint aside, the pianist can do no wrong and has rehearsed the band well, on a set of compositions bearing his stamp, encompassing rhythm and freedom, structure and adventurous directions, perched between jazz and modern music, with contours that are never obvious to begin with, and some discernible African influence early on. One such piece is 'Generous Souls' from his 2022 album “Break a Vase”, another is a dreamy tune reminiscent of Wayne Shorter. Camila Nebbia provides inspired solos on a great sounding tenor, with Francesca Remigi on drums and guitarist Giacomo Zanus also using electronics. Duet and trio associations make up the bulk of the set. Hawkins pays tribute to Gerry Hemingway, “one of the best composers for quintet” and to Myra Melford, both seated in the audience. 'Albert Ayler, his life was too short' stems from composer Leroy Jenkins and his Equal Interest trio with Melford and Joseph Jarman, and makes for a great finale. The long and winding piece is atmospheric at first, with a solo intro from Nebbia and scattered sounds from inside the piano, then rises to insurrection levels with buzzing electronics and layered noise from the guitar, Hawkins stirring the band to a fireworks display. On the following day at noon, Hawkins’ solid bassist Ferdinando Romano presents his “Invisible Painters” band at the Cortile Palazzo Tornielli. We’re into European jazz territory, alternating or maybe hesitating between contemplative pieces and rhythmic workouts. While there is no shortage of skills, the project needs to be better defined, the liberal and fashionable use of electronics not being necessarily the best way to go about it.

|

| Joëlle Léandre |

The following morning starts with a solo at Galleria Giannoni. Joëlle Léandre is presented with a Golden Key to the city. This award follows the French double bassist recognition at last year's Vision festival in New York. She gives a speech about learning, unlearning, discovering free jazz at the American Center in Paris, and talks about her lifelong quest to becoming herself. “Be you!”, she likes to encourage others. In his liner notes to the box set A Woman’s Work, Stuart Broomer writes: “Above all, the great improviser practices, we might assume, the habit of inspiration, (…) but also, one suspects, the ability to profit from boredom, distraction, even irritation.” Whatever mood she’s in, whatever the playing conditions are, Léandre knows no fear of the blank page and is able to tap into an endless well of instant inspiration, only needing a few seconds’ focus to delve into each successive piece. This also involves reliance on memory – maybe this is not said enough – in order to give each track a shape and flavor, an entity with a beginning, middle and end. Such is the art of the improviser and our bassist embodies it, making use of a keen sense of timing and connection to the audience, including laughter and derision. She is driven and her discourse ever relevant, helped by flawless technique to express her ideas. I wonder, aren’t Léandre’s solos really duets, with their inclusion of spontaneous vocals? Somewhere between opera singer and Native American sorcerer, Léandre whispers, whimpers and rumbles, accompanying a drone kept alive with the bow.

|

| Myra Melford |

The inner courtyard of Palazzo Bellini is where pianist Myra Melford shows up unaccompanied – a rare occasion. Once more I’m struck with the vigorous, fierce attack on the keys, the rhythmic impulse noticeable even in the more abstract moments. These are written compositions and each one feels like an adventure, a plunge in a waterfall, full of dangers and unexpected wonders. The writing is highly evolved yet deeply rooted in jazz and blues, with the early influence of Don Pullen and Henry Threadgill still felt. Other recurring sources of inspiration come from painting and literature. Melford plays her own music, not standards, although it is possible to hear some echoes of Gershwin in there too. The palette is as broad as it is precise in its intentions and implementation. And proof that formal innovation can be attained without electronics. Not a hint of mawkishness here, but a tumultuous lyricism instead. Some pieces are faster than the speed of light, all hammered eighth-notes and hefty clusters in the low register. Like timeless tableaux, Melford's tunes are so rich one would have to study them at length and from different perspectives to grasp all the nuances they withhold.

|

| Pasquale Mirra |

The Italian trio of piccolo trumpeter and flautist

Gabriele Mitelli, vibraphonist Pasquale Mirra and drummer

Cristiano Calcagnile

(all three also on vocals) plays next. 'The Elephant' is

spaced-out electro-jazz-rock, very much a satellite project to Rob

Mazurek’s Exploding Star Orchestra, which doesn’t come as a surprise since

both Mirra and Mitelli are collaborators of the Chicago trumpeter and

composer. An electronic motif serving as the basis for a track resembles

that of Disco 3000 by Sun Ra, while other pieces lean on binary

grooves, sometimes close to hip-hop. Ambient soundscapes lead to a showcase

for the drummer, while Mitelli’s brief bursts rely on extended techniques

and take precedence over jazz phrasing, when he doesn’t entirely put down

his instruments to concentrate on sound effects.

|

| Guus Janssen |

Dutch pianist and improviser Guus Janssen treats us to an organ recital at the Church of San Giovanni Decollato, titled 'Le direzioni del vento (Directions of the wind).' Away with conventions: it’s playful, irreverent, funny, from classical music pastiches to recurring quotes of the Spiderman theme song from the late 70s TV show. The virtuoso jumps from unabashedly repetitive chords mocking – affectionately we surmise – caricatural rock and roll and psychedelic pop. The whole zany thing is presented with the utmost seriousness and rings beautifully in the chapel where ancient fresco reliefs remain. The organ manages to evoke bagpipes and a cow mooing at some point, before an official-sounding anthem is put to the test by incongruous inserts. The extraordinary solo set has everyone in fits before the mood gets darker with a song by an Italian composer as a paean to silence, and for the encore, a piece by a Dutch composer, inspired by the moon and to which the veteran scamp – who has a speaking voice not unlike that of Max von Sydow – adds an epic ending.

|

| Rodrigo Amado |

Another solo was also a highlight of this edition. Lisbon’s Rodrigo Amado's (tenor sax) set was planned to happen in the towering Basilica di San Gaudenzio but was relocated to Sala dell’Arengo. The musician was able to visit the space on the previous day and was not only reassured, but enthused by its acoustic properties. In 2022, Amado released Refraction solo. Busy with trios and quartets, he rarely performs alone and relishes the opportunity. He engages in open idiomatic improvisation, organized, melodic, textured, unhurried, the unfolding more linear than choppy. The first improvisation is a variation on Sonny Rollins’ Freedom Now Suite. When Amado tilts the horn's bell towards the seated folk, the sound hits like a gust of wind, a reminder that he’s a powerful player. Other points of departure for Amado’s flights of imagination are Albert Ayler’s “Ghosts” and the spiritual “There is a balm in Gilead”. One of the most consistently stimulating saxophonists of this century, with a great knowledge about the history of the music and a vivid creativity to push it forward.

|

| François Houle |

'Faded Yellow', 'Dragon’s blood' , 'Green – Absynthe', 'Umber', 'Heliotrope' and 'Azure' are François Houle Quintet “The Secret Lives of Color” titles, actually improvisations with minimal directions such as the order of tutti, duos and trios. Joining the clarinet player from Canada are Myra Melford, Gordon Grdina, Joëlle Léandre, and Gerry Hemingway on drums: not your everyday line-up! At the foot of the towering Duomo, the audience is invited to sit in the grass, while the group plays under the arches of the rectory, protected from a menacing rainstorm. After an introduction from the leader, a series of surges and lulls ensue. For most of the duration the music is, maybe surprisingly, subdued, to the point that one also hears the doves in the trees, birds fighting on the ancient tiled roofs, and the humming of disoriented bees' wings, whose dwelling place we are disturbing. Grdina shines on guitar then oud, and Houle extracts some mysterious flute sounds from the clarinet. Hemingway caresses the percussion rather than strikes it, and is also heard on harmonica, vocals and whistle, while Léandre and Melford are careful of serving the collective poetry. The musicians have history together, which explains why this quintet came to be, the telepathic connection of its members and the emotional state of the leader at the end of the set: Joëlle and Myra are two thirds of the Tiger trio, Gerry Hemingway played in groups with Joëlle and Myra separately, Canadians Houle and Grdina recorded several albums together, such as Ghost Lights in 2017 and Recoder in 2020 (with Gerry Hemingway and Mark Helias), while Houle and Léandre had a trio with Raymond Strid (issued on 9 Moments in 2007) and with Benoît Delbecq on 14, rue Paul Fort, on Leo Records in 2015. So that's a lot of threads, travels and experiences coming together today in Novara.

|

| The Secret Lives of Color + festival organizers |

Thursday, August 6, 2020

Scene Spotlight: Sidebar (New Orleans, LA)

|

| Andy Durta, booking manager for the New Orleans club Sidebar with Ken Vandermark |

By Nick Ostrum

I first dropped the idea of an interview to Andy Durta, booking manager for the New Orleans club Sidebar, at the end of 2019. I had envisioned a quick discussion about the New Orleans improv scene and Sidebar’s unique place within it. Coming around the 3 rd anniversary of the Scatterjazz music series at venue and just before the venue, bar included, celebrates its 5th anniversary this August, I had originally thought the discussion would be somewhat more triumphant than what transpired when Andy and I finally got to sit down on Zoom on May 30. By then, we (New Orleans) had been under quarantine for two months. Andy and Sidebar mastermind Keith Magruder had meanwhile converted all of Sidebar’s programming first to audience-less performances in the venue itself, then to DIY live streams from people’s living rooms and attics. In true New Orleans fashion, these shows broadcast for free with an encouraged donation to the artists and venue.

Many of you may have visited New Orleans in the past. If you were really committed, you might have spent some time searching the free papers or online for non-traditional venues and acts with the hopes of eschewing the throngs of Frenchman Street. And, if the stars aligned, you might have come across shows with the likes of Jeff Albert, Tristan Gianola and Jason Mingledorf (three local jazzers) or Gordon Grdina (Vancouver) with Simon Berz (Switzerland) and Cyrus Nabipoor (New Orleans) or Tim Berne (New York), James Singleton and Aurora Nealand (both of New Orleans). Add another Gordon Grdina night and a trio with local lap-guitar wizard Dave Easley, and these are the first shows I attended at Sidebar. And this spread of musicians was hardly a fluke. Instead, it is emblematic of what the venue has so effectively offered. A local club, most of its shows consist of New Orleans-based musicians, many of whom have made their name in other musical circles but have meanwhile maintained a deep interest in experimental music. Think: Nealand and Albert, the New Orleans Klezmer All-Stars, Nicholas Payton, and, of course, the incomparable Kidd Jordan. Often enough, Andy is also able to get national and international musicians – ranging from Berne and Grdina to Frank Gratkowski, Ingrid Laubrock, and the Humanization 4tet – to join these locals and create some pretty magical evenings.

Alright. This is too quickly turning into a love letter to a club and a time temporarily past, so I will get to the point. I am not exaggerating when I say that in just five years, Sidebar has become the epicenter of free jazz in New Orleans and Andy Durta has been central to that process. The interview above is somewhat sprawling. It starts with a recent show by Swedish concert-hall trombonist Elias Faingersh and wends into stories about years of concert organizing, gratifying passages of name-dropping, and an interesting claim about how many of the most exciting shows that Andy has organized have simply “fallen into (his) lap.” More seriously, the interview also digs into some of the real challenges and frustrations of organizing shows both before and during Covid, and the merits of the struggle to keep improvised music live and accessible. And, if you bear with us for the entire hour, you will hear some colorful stories about Andy and Louis Moholo as they raced to the Yells at Eels show that Ayler Records would later release as Cape of Storms, as well as some beautiful final thoughts.

NB: This interview was recorded at the end of May. The references to upcoming events are therefore outdated. However, I just got word that the Sidebar is celebrating its fifth anniversary with a Webathon of performances from some local jazz and blues musicians (including the local legend Walter “Wolfman” Washington) and sprinkling of more progressive players such as Isabelle Duthoit & Franz Hautzinger, both of whom are featured in the interview. Shows will run August 7-9. Afterwards, the venue will go quiet for a few weeks as Keith and Andy take a well-deserved break. Here’s hoping the hiatus does not last too long.

Free = liberated from social, historical, psychological and musical constraints

Jazz = improvised music for heart, body and mind

Popular Posts this Year

-

Les Victoires du jazz are a French annual awards ceremony devoted to Jazz . For the 2017 edition, which took place last month, all the...

-

Drawing by Anjali Grant Dear readers, Thank you for another year of being a part of the Free Jazz Collective! According to our statis...

-

Photo by Peter Gannushkin By Martin Schray Some news simply comes out of nowhere, it catches us unprepared and on the wrong foot. ...

-

We are happy to announce the Free Jazz Collective's top album of 2024. Last week, we presented the top 10 recordings of the year, culled...

-

By Stuart Broomer Evan Parker and Matt Wright have been working together since 2008. Wright initially contacted Parker to ex...

Tags

- *****

- 7"

- Accordion

- Acousmatic

- Africa

- Album of the Year

- Alphabetical Overview Of All CD Reviews

- Ambient

- Analog Synthesizer

- announcement

- Avant-Folk

- Avant-Garde

- Avant-garde jazz

- Avant-rock

- Balkan jazz

- Baritone Sax & Viola Duo

- Bass Bass duo

- Bass-drums duo

- Bass-Flute Duo

- Bassoon

- Big band

- Book

- Brass

- cassette

- Cello

- Cello-Bass Duo

- Cello-Drums Duo

- Cello-sax-sax trio

- Chamber Jazz

- Chamber Music

- Chicago

- Clarinet Piano Duo

- Clarinet quartet

- Clarinet quintet

- Clarinet Trio

- Clarinet-bass duo

- Clarinet-bass-drums

- Clarinet-clarinet duo

- Clarinet-Cornet Duo

- Clarinet-drums duo

- Clarinet-flute-piano Trio

- Clarinet-Guitar Duo

- Clarinet-sax duo

- Clarinet-trumpet duo

- Clarinet-vibes-bass Trio

- Clarinet-viola-bass trio

- Clarinet-violin duo

- Clarinet-voice duo

- Classical

- Concert Review

- Contemporary

- Corona Diaries

- Deep Dive

- Deep Listening

- Doom jazz

- Drone

- Duos

- DVD

- echtzeit@30

- Electroacoustic

- Electronics

- Evaluation Criteria

- Evan Parker @ 80

- Experimental

- feature

- Festival

- Festival Calendar

- Film

- Film music

- Flute-percussion duo

- Free fusion

- Free Jazz Top 10 2006

- Free Jazz Top 10 2007

- Free Jazz Top 10 2008

- Free Jazz Top 10 2009

- Free Jazz Top 10 2010

- Free Jazz Top 10 2011

- Free Jazz Top 10 2012

- Free Jazz Top 10 2013

- Free Jazz Top 10 2014

- Free Jazz Top 10 2015

- Free Jazz Top 10 2016

- Free Jazz Top 10 2017

- Free Jazz Top 10 2018

- Free Jazz Top 10 2019

- Free Jazz Top 10 2020

- Free Jazz Top 10 2021

- Free Jazz Top 10 2022

- Free Jazz Top 10 2023

- Free Jazz Top 10 2024

- Fringes of Jazz

- Fusion

- General

- German Festivals

- Guitar Trio

- Guitar Trombone Duo

- Guitar Week

- Guitar-bass Duo

- Guitar-Flute Duo

- Guitar-percussion duo

- Guitar-Piano-Sax/Clarinet Trio

- Guitar-Viola Duo

- Guitars

- HAPPY NEW EARS 2010

- HAPPY NEW EARS 2011

- HAPPY NEW EARS 2012

- HAPPY NEW EARS 2013

- HAPPY NEW EARS 2014

- HAPPY NEW EARS 2015

- HAPPY NEW EARS 2016

- HAPPY NEW EARS 2017

- HAPPY NEW EARS 2018

- Harp

- Harp Trombone Duo

- Holiday Music

- Industrial

- Information Sources

- Interview

- Jazz Novels

- John Zorn Birthday Week

- Keyboard-Drums duo

- Large Ensemble

- Lonely Woman

- Mainstream

- Metal Jazz

- Minimalism

- Modern jazz

- Musicians Of The Year 2008

- Musicians Of The Year 2009

- Musicians Of The Year 2010

- Musicians Of The Year 2012

- Musicians Of The Year 2013

- My scoring system

- Noise

- Nu Jazz

- Organ

- Organ bass duo

- Organ percussion duo

- Organ Trio

- Organ-Sax duo

- Oud

- Percussion Duo

- Percussion-Vocals Duo

- Piano Bass Bass Trio

- Piano Bass Cello Trio

- Piano Bass Duo

- Piano Cello Duo

- Piano Drums Duo

- Piano Duo

- Piano Electronics Duo; Piano

- Piano Guitar Drums Trio

- Piano Guitar Duo

- Piano Percussion Duo

- Piano Trio

- Piano Vibraphone Duo

- Piano Viola Duo

- Piano Violin duo

- Pianos

- Poetry In Jazz

- Polish Jazz Week

- Portrait

- Post-jazz

- Post-rock

- Promo

- Psychedelic jazz

- Quick Review

- Re-issue

- Reeds Duo

- Review Team

- Reviewer

- Rock

- Roundup

- Sax and Electronics

- Sax Cello Drums

- Sax organ duo

- Sax Piano Bass Trio

- Sax piano cello trio

- Sax Piano Drums Trio

- Sax Piano Duo

- Sax quartet

- Sax quintet

- Sax trio

- Sax-bass Duo

- Sax-cello duo

- Sax-drums duo

- Sax-drums-guitar

- Sax-guitar duo

- Sax-guitar-drums trio

- Sax-harp duo

- Sax-organ duo

- Sax-piano-bass Trio

- Sax-sax duo

- Sax-trumpet duo

- Sax-trumpet-guitar

- Sax-Vibes-Bass Trio

- Sax-violin duo

- sheet music

- Skronk

- Solo Bass

- Solo Bass Sax

- Solo Bassoon

- Solo Cello

- Solo Clarinet

- solo flute

- Solo Guitar

- Solo Oboe

- Solo Percussion

- Solo Piano

- Solo Sax

- Solo Trombone

- Solo Trumpet

- Solo Tuba

- Solo Viola

- Solo Violin

- Soundtrack

- Streaming

- String Duets

- String Ensemble

- Sunday Interview

- Sunday Video

- Techno

- Top 10 Lists

- Top 20 Free Jazz of All Times

- tribute

- Tribute Album

- Trombone

- Trombone trio

- Trombone-bass duo

- Trombone-Percussion duo

- Trumpet Duo

- Trumpet Guitar Bass Trio

- Trumpet quartet

- Trumpet trio

- Trumpet-bass Duo

- Trumpet-cello Duo

- Trumpet-drums duo

- Trumpet-guitar duo

- Trumpet-guitar-percussion Trio

- Trumpet-guitar-piano

- Trumpet-Harp Duo

- Trumpet-percussion

- Trumpet-piano duo

- Trumpet-piano-drums Trio

- Trumpet-piano-percussion Trio

- Trumpet-trombone duo

- Trumpet-trumpet Duo

- Trumpet-vocal Duo

- Tuba

- Tuba Sax Trumpet

- Vibraphone

- Vibraphone-Saxophone Duo

- Video

- Video Premiere

- Violin Trio

- Violin-bass duo

- Violin-bassoon duo

- Violin-cello duo

- Violin-drums duo

- Vocal

- Weekend Roundup

- Women In Improv

- Woodwinds

- World Jazz

- World Jazz Top 10 2006

- World Jazz Top 10 2007

(FREE) JAZZ LINKS

- All About Jazz

- All Music Guide

- Avant Music News

- Burning Ambulance

- Cardboard Music

- Diana Deutsch's Audio Illusions

- Draai Om Je Oren (Dutch)

- El Intruso

- Improvised

- Jazz And Assorted Candy

- Jazz Corner

- Jazz Frisson (Canadian French)

- Jazz My Two Cents Worth

- Jazz Viking (in French)

- Keep Swinging!!!

- Le Son Du Grisli (French)

- Master Of A Small House

- Perfect Sounds

- Scaruffi's history of free jazz

- Sound American

- The Paradigm for Beauty

- Tune Up

Blog Archive

-

▼

2025

(251)

-

▼

September

(14)

- Christian Pouget: Maëlstrom for Improvisers

- Zoh Amba - Sun (Smalltown Supersound, 2025)

- Jazzfestival Saalfelden 2025 (4/4)

- Jazzfestival Saalfelden 2025 (3/4)

- Jazzfestival Saalfelden 2025 (2/4)

- Jazzfestival Saalfelden 2025 (1/4)

- Festival MÉTÉO Mulhouse 20 - 23 August

- Die Hochstapler live at Manufaktur Schorndorf 9/5/...

- Julien Desprez - The body, electricity, and politics

- Joe McPhee, Susanna Gartmayer, Joe Edwards, Mariá ...

- What's happening in the trees? The musical univers...

- Jazz em Agosto / Lisbon, August 1-10 (3/3)

- Jazz em Agosto / Lisbon, August 1-10 (2/3)

- Jazz em Agosto / Lisbon, August 1-10 (1/3)

-

▼

September

(14)